Regenerative Agriculture: to Invest or not to Invest?

- Axel

- Oct 9, 2024

- 15 min read

Updated: Nov 8, 2025

Regenerative agriculture plays a critical role in addressing the systemic risks facing global food supply chains. With agriculture contributing significantly to environmental degradation, investing in regenerative practices presents a viable solution for mitigating climate risks, enhancing productivity, and ensuring long-term profitability. Through real-options analysis, we demonstrate how companies can adapt to uncertainty and leverage opportunities for growth by integrating regenerative agriculture into their procurement strategies. Collaboration across value chains and sectors, coupled with robust data systems, is essential for building resilient food systems that benefit both businesses and the environment.

The $350 Billion Question

Agriculture: The Next Critical Frontier in Addressing Climate Change

For decades, climate and energy have been the primary focus in addressing climate change. Now, agriculture is emerging as the next critical frontier. Given its significant impact on planetary boundaries and its potential to combat climate change while restoring ecosystems, the transformation of global food systems is imperative.

Food production alone is responsible for 34% of global greenhouse gas emissions (1), 70% of freshwater use (2), and 90% of deforestation (3). It is also a leading cause of biodiversity loss and the eutrophication of river basins and coastal areas (4)(5). In a stark warning three years ago, the FAO declared that our food systems were "on the brink of failure", and with 50% of soils already degraded, a figure that could soar to 90% by 2050 if current practices persist, the need for change is clear (6)(7).

The urgency to rethink how we produce, process, distribute, consume, and dispose of food has never been greater. This transformation is not only essential for environmental sustainability but also for human and planetary health.

Systemic Threats to Food Value Chains

Environmental challenges do not exist in isolation; they amplify each other, leading to broader systemic risks that can destabilize entire food systems, economies, and ecosystems (8). All these systemic threats, the consequences of which will cascade through feedback loops between terrestrial compartments, jeopardize the entire value chain and our own ability to ensure our food supply. Industry players are already contending with physical and transitional risks: since 2014, agricultural commodities like cotton, wheat, corn, rice, and soybeans have experienced recurrent economic shocks, compounded by extreme weather events, political instability, and health crises (9).

To illustrate the growing vulnerability of global food supply chains to climate change, extreme weather events, and rising energy costs, let’s examine some examples:

In France, supermarkets experienced a 10% shortage in stock in the summer of 2023, five times the usual rate. Excluding cases of panic buying, this led to sector losses of €1.9 billion, driven by climate events (potatoes, rice), pandemics (poultry), and rising energy costs (transport, storage, etc.) (10) (11).

In India, fast-food giants like Burger King, McDonald's, and Subway removed tomatoes from their burgers due to severe shortages caused by extreme weather and skyrocketing raw material prices (12).

In the UK, McDonald's reduced the number of tomato slices in its Big Tasty burger from two to one, citing weather issues in Morocco and Spain, as well as rising energy costs in British and Dutch greenhouses (13).

Orange juice futures on the London Stock Exchange have doubled since the beginning of 2024 due to fears of future shortages. Hurricanes and frost waves in Florida (2022) and droughts in Brazil (2023) have only served to compound existing issues. Florida, which accounted for 80% of the world’s orange production 20 years ago, saw its production collapse by 93% due to the contamination of orange groves by citrus greening disease. Now, Brazil is beginning to face similar pest-related challenges due to climate change (14).

These examples highlight how disruptions in agricultural production and supply can lead to significant economic losses, shortages, and operational challenges across industries. The cases show that no region or sector is immune to these risks, emphasizing the need for businesses to adapt their sourcing strategies and invest in resilience, such as regenerative agriculture, to mitigate the impact of these increasingly frequent disruptions.

Food value chains are increasingly recognizing that the status quo is unsustainable. A study by FoodDrink Europe revealed that the cost of transforming food systems in the first year is estimated at €28-35 billion, while the cost of inaction could reach €50 billion annually (15). This calls for a collective effort across food systems to invest in resilience, sustainability, and the long-term stability of global food supply chains.

Regenerative Agriculture: Paving the Way for Mainstream Scope 3 Decarbonization

Regenerative agriculture, while widely discussed, has yet to be clearly defined. It is one of various steps on the agroecological ladder toward integrated ecosystem services, alongside practices such as organic farming, conservation agriculture, agroforestry, and permaculture. Scientific institutions have yet to adopt a unified position on regenerative agriculture, instead focusing on key agricultural practices with proven and measurable positive outcomes.

Despite this diversity, a new movement has already taken root across Europe: a study by the Climate Agriculture Alliance found that over 9,500 farmers across 18 EU countries are now managing 4.7 million hectares of land, collectively reducing and storing nearly 15 million tonnes of CO2 equivalents in soils (16). Agricultural practices, their impacts, and the business cases supporting them are becoming increasingly well-documented. Over the last 5-to-10 years, large corporations have implemented programs for their suppliers and dedicated significant investments to these efforts, while business coalitions have also developed comprehensive guidance (17) (18) (19).

McCain is one example of a corporation taking meaningful action toward regenerative agriculture. The company has entered into a three-year sourcing contract that offers a premium to farmers who adopt regenerative practices. In collaboration with Rabobank for financial support and Wageningen University for technical training, McCain is actively supporting farmers in this transition. Initial results show that yields have remained relatively stable compared to conventional farming, with some instances of increased resilience during extreme weather events, such as droughts.

On the carbon front, McCain aims to sequester 0.2 to 1 ton of CO2 equivalent per hectare in the initial phase (20). Technologies that help farmers adopt and measure the outcomes of these new practices are already in place, and advancements in artificial intelligence make it possible to envisage even more promising developments.

While these early results are promising, the path forwards from a value chain perspective remains complex. Many sustainability teams within companies still operate in isolation from core operations, making it difficult to fully integrate sustainable practices into purchasing strategies or supplier relationships. As a result, supply chain security has yet to become a central focus for most organizations, despite the clear benefits of doing so.

Political Momentum Behind Regenerative Agriculture

Regenerative agriculture has gained significant political momentum within European institutions, marked by key milestones such as the adoption of the Carbon Removal Certification Framework (21), and the directive on empowering consumers for the green transition (22). Ongoing developments include the examination of the Green Claims Directive (23), and the Soil Health Monitoring Law (24).

Had it not been for the farmers’ riots in early 2024 and the upcoming elections, the Framework for Sustainable Food Systems, introducing for the first time a holistic approach to transforming the entire value chain by integrating environmental, agricultural, and health policies, would likely be under consideration by co-legislators today. However, results from the expert group on the Future of EU Agriculture (25) lay the groundwork for a new collective ambition and the next EU Commission, set to begin in 2025, which are expected to take significant steps in this direction.

Building the Business Case for Engaging Value Chains in Regenerative Agriculture

Profitability of Regenerative Agriculture: A Missed Opportunity for Value Chains

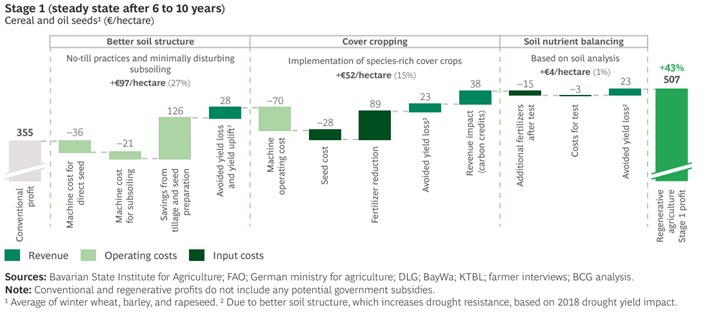

Business and scientific literature provides substantial evidence that regenerative agriculture is profitable for farmers (26)(27)(28). Numerous farm-level studies have demonstrated not only the environmental benefits of regenerative practices, but also their economic viability. Production costs, particularly those related to lower input use, reduced soil disturbance, and fewer labour hours, are consistently reduced by 10% to 20%. Furthermore, regenerative agriculture is widely recognized for its resilience in the face of climatic, biological, economic, and geopolitical risks (29), and, in most cases, farm productivity is either maintained or improved compared to traditional farming.

However, to our surprise, there has been little effort to demonstrate that investing in regenerative practices across the value chain—by cooperatives, corporations, and distributors—can also lead to increased profitability and operational continuity. This is a crucial oversight, as experts estimate that scaling regenerative practices requires an investment of $350 billion annually, a cost that must largely be borne by value chain stakeholders (30).

Incorporating Uncertainty into Investment Decisions: The Power of Real-Options Analysis

To answer these questions, our team conducted a real-options analysis for a large multinational that is a market leader and actively working towards carbon neutrality. Focusing on its wheat supply in Central Europe, we developed multiple scenarios that explore changes in production conditions, prices, and volatility. We also integrated regulatory and market considerations, such as evolving consumer demand and carbon pricing, across three key time horizons: 2030, 2040, and 2050.

To inform our analysis, we gathered internal data, conducted interviews with various business units, and consulted scientific literature and industry reports (see references).

We used real-options analysis to compare two plausible trajectories:

1. The business-as-usual scenario: based on conventional agriculture and international trade.

2. The alternative: anchored in the conversion of all suppliers to regenerative agriculture and direct sourcing through contractualization.

Traditional investment decision-making models rely on a straightforward cost-benefit analysis over a fixed period. Free cash flows are discounted to the present date to determine the net present value (NPV), which, along with the internal rate of return (IRR) and the break-even point, guides the decision: to invest or not. While effective under stable and predictable conditions, this model has limitations when circumstances shift. It assesses risks, costs, and benefits ex-ante and provides a binary outcome—invest or not—committing resources once and for all. Once the project is initiated, it must deliver the expected value regardless of how external factors evolve.

In contrast, real options analysis offers greater flexibility. It accounts for uncertainty, allowing for adjustments as conditions change. This approach enables investors to mitigate risks and seize new opportunities as they arise, making it more adaptive to dynamic environments.

Real options analysis provides a framework for making informed decisions based on up-to-date information, offering the flexibility to delay, extend, scale back, or abandon a project as conditions evolve. This method is grounded in the same principles as financial options, notably the Black-Scholes model introduced in 1973, which revolutionized financial mathematics in the 1980s. Today, real options analysis is increasingly used by economists and development banks to evaluate investments related to climate change adaptation (31)(32).

Unlike traditional cost-benefit analysis, which discounts a single expected trajectory of future Free Cash Flows (FCF), real options analysis accounts for multiple scenarios by discounting the full range of potential outcomes—known as "uncertainty cones"—each weighted by its probability. This approach provides a more nuanced estimate of Net Present Value (NPV), reflecting the inherent uncertainty of future conditions (33).

Results

Based on a procurement volume of 100,000 tons annually, our analysis indicates that the additional costs of sourcing could range from €19 million to €118 million per year by 2050 under a business-as-usual scenario. Notably, the narrow gap between the best-case and medium-case scenarios suggests that there is no foreseeable improvement over time – companies are doomed to choose between losing less or losing more.

The primary drivers of these cash flow trajectories are the rising commodity prices, which are projected to increase by 2.5 times by 2040 (33), the growing volatility of international markets (28)(9), and the potential integration of carbon costs into regulated markets, such as the Emission Trading System (ETS) (35)(36)(37).

In contrast, investing today in regenerative agriculture and adapting supply strategies to global volatility could significantly mitigate losses – ranging from a worst-case scenario of a €28 million loss to potential additional cash flows of €16 million annually by 2050. Both the best-case and medium-case scenarios offer clear financial benefits for the company.

Though initial investments are required to support farmers in their transition, break-even could be achieved quickly (within 4 to 5 years), even when factoring in incentives paid to farmers for adopting regenerative practices.

When translated into Net Present Value (NPV) to assess the return on investment, the business-as-usual scenario reveals a staggering negative NPV of €264 million, while the regenerative agriculture scenario results in a far more manageable loss of just €1.5 million. In other words, the cost of doing nothing is equivalent to losing €264 million today.

Conversely, any investment in regenerative agriculture is expected to be profitable, as long as it remains below this €264 million maximum threshold.

Business Perspectives

Invest Now, even if the Future is Unclear

In our analysis of sourcing 100,000 tons of wheat in a single Central European region, we encountered scenarios that may initially appear overly broad or pessimistic. Indeed, we deliberately adopted high assumptions to account for future uncertainties. While the data is rooted in scientific research, some systemic parameters—such as recovery lags (the years needed to financially rebound after a disaster), tipping points (e.g., when multiple shocks drive farmers out of business), and cascading disruptions in supply chains from simultaneous events—are difficult to quantify. As a 2024 paper published by Science Advances states, "uncertainties are too large to predict tipping points" (38).

With increasing supply chain disruptions, securitization is becoming a critical issue. Traditional risk-sharing strategies, like hedging, are losing their effectiveness due to the growing frequency and simultaneity of extreme events. In a world of rising disasters, competition in the industry will increasingly depend on a company's ability to secure its supply chain by investing today. Those who fail to act quickly may soon find themselves out of business.

While regenerative agriculture offers clear benefits, it also raises important questions regarding the robustness of methodologies, the accessibility of MRV (Measurement, Reporting, Verification) systems, and the “living” uncertainty in the link between practice and impact, etc. However, given the credibility of more and more extreme scenarios, as well as the time required (up to 8 years) to fully realize the scope and impacts of regenerative strategies, the sooner companies invest in their supply chains, the quicker they can learn, adapt, and safeguard against future disruptions.

Measuring What Matters: Data Collection & Analysis in a Volatile World

Let us be clear: collecting the right data is a key challenge when building projections, particularly for future commodity prices. Most companies lack the capacity to routinely monitor and collect the necessary data, making this a crucial yet precarious task. Historical data offers only limited insight into the future, and, as we observed in our case study, there is often no clear correlation between changing parameters and their impact on cash flows or costs. In a rapidly changing environment, the only viable approach is to build plausible scenarios and accept the wide variability in potential outcomes.

Investment decisions must increasingly incorporate models that account for uncertainty, such as Real Options Analysis. While other models also provide valuable insights (38), they need to be supported by accurate and relevant data. One of the first investments towards sustainable value chains should focus on strengthening internal capabilities to foster closer relationships with key stakeholders (suppliers, farmers, etc.) and building a broad range of plausible future scenarios, as recommended by organizations like the IPCC and the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (39)(40).

Beyond changing how “companies view the world”, Real Options Analysis is a leadership exercise. It challenges decision-makers to assess uncertain outcomes, identify weak signals, understand feedback loops, and recognize tipping points within complex systems.

Investing in Regenerative Agriculture: A Collective Effort for Greater Impact

Although the cash flow projections examined in this article may seem alarming, they serve more as a wake-up call than a definitive estimate of the investments required. Supporting farmers on their regenerative journey is far less costly, and we estimate that economies of scale can quickly be reached, especially when it comes to reducing upfront costs by engaging more farmers or improving the return of fixed costs of programs like MRV, advisory services, and training etc.).

Given the uncertainty on one hand, and the multiple co-benefits and potential valuations on the other, this underscores the need for collaboration. Building partnerships across industries and the entire value chain – from upstream to downstream players, including public authorities – can pool risks, expertise, resources, and market opportunities. Blended finance and place-based solutions have already demonstrated economic, environmental, and community value, and these approaches are increasingly becoming institutionalized.

The transition of agricultural practices at both the territory and commodity level is a shared responsibility between public and private stakeholders, particularly when it comes to providing the financial resources needed to implement and scale these practices. Regenerative agriculture not only enhances climate resilience and optimizes production costs, but also offers widespread benefits for all players in the agricultural sector, right through to the end consumer.

Regenerative agriculture is financially sustainable because it is resolutely productive. However, it also requires a partnership approach to mitigate market-driven price volatility. Long-term procurement contracts based on guaranteed income for producers (cost-based model rather than market-price-alone models) and investments driven by funds with shared governance and risk can seem complex to implement, but today we are well-equipped to meet this challenge.

Indeed, value chain analysis should help clarify the risks, guiding strategic decisions related to procurement policies, particularly for production companies which must integrate new collaborative practices with all players while still achieving their productivity goals. Over and above these purchasing policies, supporting the Just Transition (41) of agricultural practices towards regenerative agriculture opens the door to new value propositions for companies and consumers alike.

This brings us back to the fundamental question of leadership, of entrepreneurship in the service of the common good, and of the interdependence between common and private interests. Many initiatives have already shown that transitional leadership is not only possible but expected, and there are already regulations in place to support this. It takes a cycle of between 5 and 8 years to regenerate the soil; we cannot wait for further food crises to threaten global stability before we act!

References

1. Food systems are responsible for a third of global anthropogenic GHG emissions. Crippa, M, et al. 2, 2021, Nature Food, pp. 198-209.

2. FAO. L'Etat des ressources en terres et en eau pour l'alimentation et l'agriculture dans le monde - Des systèmes au bord de la rupture. Rome: s.n., 2021. Rapport de synthèse 2021.

3. WWF. Threats: deforestation and forest degradation. Overview. WWF. https://www.worldwildlife.org/threats/deforestation-and-forest-degradation.

4. IPBES. Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services. Bonn, Germany: IPBES Secretariat, 2019. Summary for policymakers.

5. European Environment Agency. Water and agriculture: towards sustainable solutions. Copenhagen: Publications Office of the European Union, 2021.

6. Röckström, Joahn. How can we transform the global food system to preserve our planet? Euronews. 5 juill. 2023.

7. United Nations. Food Systems Summit 2021. United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/food-systems-summit/about.

8. Shock transmission in the International Food Trade Network. Distefano, Tiziano, et al. 8 août 2018, PlOS ONE.

9. World Economic Forum. How a radical idea could protect our food supply chains from climate events. World Economic Forum. 30 nov. 2023. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/11/adaptation-protect-supply-chains-climate-change-cop28/.

10. Gamberini, Giulietta. Alimentation : les ruptures d'approvisionnement en magasins ont déjà coûté 1,9 milliard d'euros. La Tribune. 19 juill. 2022.

11. Justet, M., et al. Alimentation : les ruptures de stock se multiplient dans les supermarchés. Franceinfo. 25 oct. 2022.

12. Déléaz, Thibaut. Burger King et McDonald’s retirent les tomates de leurs burgers en Inde à cause de l’inflation. le Figaro. 18 août 2023.

13. Khatsenkova, Sophia. Pourquoi y-a-t-il une pénurie de tomates au Royaume-Uni ? Euronews. 23 fév. 2023.

14. Savage, Susannah. Orange juice crisis prompts search for alternative fruits. Financial Times. 29 May 2024.

15. FoodDrink Europe. Funding the EU transition to more sustainable agriculture: discussion paper. 2023.

16. Climate Agriculture Alliance. Climate Agriculture Alliance Structures Itself to Drive Agrcultural Transition in the EU. Press release. 24 Feb. 2024.

17. BCG OP2B WBCSD. Cultivating farmer prosperity: Investing in regenerative Agriculture. 2023.

18. WBCSD. Circular transition indicators V2.0. Metrics for business, by business. 2021.

19. WBCSD. CEO guide to food system transformation. Geneva: s.n., 2019.

20. McCain. McCain's Regenerative Agriculture Framework. McCain. jan. 2024. https://www.mccain.com/media/4594/mccain_regenag_framework_2024.pdf.

21. European commission. Operationalising an EU carbon farming initiative. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the E.U, 2021. ISBN 978-92-76-30205-6.

22. European Commission. DIRECTIVE (EU) 2024/825 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 28 February 2024 amending Directives 2005/29/EC and 2011/83/EU as regards empowering consumers for the green transition through better protection against unfair practices and through. Official Journal of the European Union. 28 Feb. 2024. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L_202400825.

23. European Commission. Proposal for a DIRECTIVE OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL on substantiation and communication of explicit environmental claims (Green Claims Directive). EUR-Lex. 22 March 2023. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2023%3A0166%3AFIN.

24. European commission. Proposal for a DIRECTIVE OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL on Soil Monitoring and Resilience (Soil Monitoring Law). EUR-Lex Access to European Union law. [Online] 5 July 2023. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:01978f53-1b4f-11ee-806b-01aa75ed71a1.0001.02/DOC_1&format=PDF.

25. European Commission. Strategic Dialogue on the Future of EU Agriculture delivers its final report to President von der Leyen. European commission-press corner. [Online] 4 Sept. 2024. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_24_4528.

26. Syngenta. Conservation agriculture initiative results show economic and environmental gains. Syngenta UK. 2021. https://www.syngenta.co.uk/stewardship/conservation-agriculture.

27. Bain & Company. Helping Farmers Shift to Regenerative Agriculture. Bain & Company. 2 déc. 2021. https://www.bain.com/insights/helping-farmers-shift-to-regenerative-agriculture/#.

28. BCG+NABU. The Case for Regenerative Agriculture in Germany-and Beyond. 2023.

29. IPES-Food. From uniformity to diversity: a paradigm shift from industrial agriculture to diversified agroecological systems. 2016.

30. The Food and Land Use Coalition. Growing better: Ten Critical Transitions to Transform Food and Land Use. 2019. p. 237p.

31. Hallegatte, Stéphane, et al. Investment Decision Making Under Deep Uncertainty: Application to Climate Change. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2012. Policy Research Working Paper. n°6193.

32. European Investment Advisory Hub. Climate Change adaptation and Economics and investment decision making in the cities. European Investment Bank & European commission. Luxembourg: s.n., 2022. p. 132p, 'How to guide' and cas studies.

33. Valuing streams of risky cashflows with risk-value models. Gleißner, Werner and Dorfleitner, Gregor. 3, 9 Feb. 2018, Journal of Risk, Vol. 20, pp. 1-27.

34. World Bank Group. Commodity Markets Outlook. The Impact of the War in Ukraine on Commodity Markets. Washington, DC: World Bank Publications, 2022. p. 58.

35. European commission. Communication from the commission to the European Parliament, Council, European Economic and Social Committee, and the Committtee of the Regions - A Farm to Fork Strategy for a fair, healthy and environmentally friendly food system. Brussels, Belgium: s.n., 5 May 2020.

36. Niranjan, Ajit. Belching livestock to incur green levy in Denmark from 2030. The Guardian. 26 June 2024.

37. Pricing agricultural emissions and rewarding climate action in the land sector. IEEP, Trinomics, ecologic & Carbon Counts. Brussels: s.n., 2023.

38. Uncertainties too large to predict tipping times of major Earth system components from historical data. Ben-Yami, Maya, et al. 31, 2, 08/2024, Science Advances, Vol. 10.

39. IPCC. 3-Developping and Applying Scenarios. Geneva: s.n., 2018.

40. Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures. Final report. Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures. Basel: Financial Stability Board, 2017.

41. International Labour Organization. Climate change and financing a just transition. International Labour Organization. 9 July 2024. https://www.ilo.org/resource/other/climate-change-and-financing-just-transition.

Agricultural diversification promotes multiple ecosystem services without compromising yield. Tamburini, Giovanni, et al. 45, 4 nov. 2020, Sciences advances, Vol. 6.

Gaudiaut, Tristan. Vers une amplification des phénomènes météo extrêmes ? Statista. 25 June 2024. https://fr.statista.com/infographie/30249/nombre-catastrophes-naturelles-evenements-meteo-extremes-recenses-par-dans-le-monde-par-type/.

Comments