Land rights, Inequalities and Political Stability.

- Axel

- Apr 3, 2025

- 4 min read

Societies that distribute land equitably tend to experience sustained growth and stability, while those dominated by elite landholders face stagnation and conflict. This article explores the historical and modern consequences of land distribution, revealing its impact on wealth distribution, social inequality, economic prosperity and political stability.

In Colombia, decades of extreme land concentration fueled one of the longest-running armed conflicts in the world. Rural elites controlled vast estates while millions of landless farmers faced poverty and displacement. The lack of access to land contributed to the rise of guerrilla groups like the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), which mobilized disenfranchised rural populations against the government. Land disputes remain at the core of instability, as efforts to redistribute land under the 2016 peace agreement continue to face resistance from powerful landowners (World Bank, 2021).

Similar patterns of land inequality have driven conflict elsewhere: the Mexican Revolution (1910–1920) erupted as peasants rebelled against an oligarchic landholding system, leading to agrarian reforms that attempted to break elite control (McBride, 1923). In contrast, nations that enacted widespread land redistribution—such as Japan (1947) and South Korea (1952)—avoided prolonged social unrest and instead leveraged equitable land ownership to fuel rapid industrialization (FAO, 2012). The history of land allocation demonstrates that economic development and political stability are fundamentally tied to how societies manage access to their most essential resource.

Land Governance and Economic Trajectories

Land has historically been the foundation of wealth, and how it has been distributed has had long-term effects on economic trajectories. In medieval Europe, feudal systems concentrated land among a small aristocracy, reinforcing rigid hierarchies. The Black Death (1347–1351) disrupted these structures by creating labour shortages, allowing peasants in parts of Northern Europe to acquire land, leading to higher wages and the emergence of market-driven economies (Herlihy, 1997; Broadberry & Gupta, 2006). In contrast, Southern Europe and Latin America maintained latifundia—large estates controlled by elites—limiting mobility and economic diversification. In the 20th century, land reforms in Japan and South Korea dismantled concentrated landholding structures, enabling rural populations to become part of the industrial economy. Conversely, nations like Brazil and Mexico, where land remained in the hands of an elite minority, continue to grapple with rural poverty and economic stagnation (FAO, 2012).

The consequences of land inequality are not only economic but also political. Land inequality has historically fueled unrest, like in Latin America or Middle East, where agrarian disputes have been central to prolonged violence. In the United States, the contrast between land distribution in the North and South shaped the conditions for the American Civil War (1861–1865). The North, characterized by smaller farms and free labour, fostered economic mobility and industrialization, whereas the South’s plantation economy, reliant on enslaved labour and concentrated land ownership, resisted these changes, deepening sectional divisions and fueling conflict. The Homestead Act (1862) sought to expand land access, yet exclusionary practices such as Black Codes and redlining created persistent racial wealth disparities (Rothstein, 2017) which are still visible today.

Modern Land Distribution and Wealth Inequality

While industrial economies have shifted wealth creation away from agriculture, the structural inequalities established through historical land distribution persist in different forms. Urban real estate ownership today mirrors historical patterns of land concentration, where elite and corporate control of housing markets exacerbates social and economic divides. Beyond property, disparities in access to social capital—such as education, professional networks, and financial credit—reinforce these inequalities, limiting economic mobility for marginalized communities and perpetuating cycles of wealth concentration and exclusion. In cities like London and New York, concentrated landownership drives housing shortages and rising costs (Piketty, 2014; Saiz, 2010). In rural areas, corporate land monopolies and agribusiness consolidation have displaced small farmers, worsening economic decline and regional disparity (USDA, 2021). In Europe, the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) attempts to address rural development and economic equity, but land concentration remains a challenge (European Commission, 2022). The governance frameworks established through centuries of land allocation continue to shape economic opportunities, reinforcing patterns of inclusion or exclusion depending on the extent of redistribution.

The Legacy of Land Governance in Modern Economies

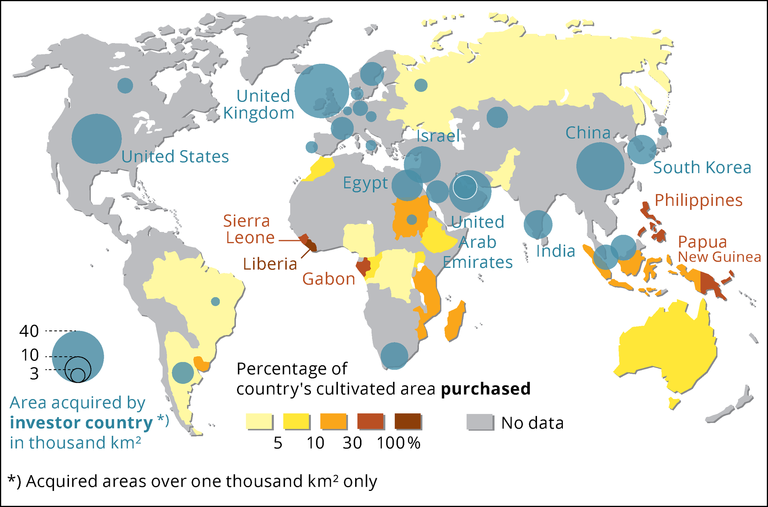

The economic structures of today still reflect land governance decisions made centuries ago. Societies that implemented equitable land distribution—whether through historical redistribution or modern policies—developed more inclusive economies, stronger middle classes, and stable political institutions. In contrast, regions that maintained elite control over land saw entrenched inequalities, economic stagnation, and higher risks of instability. As historical land policies shaped economic structures, today's challenges—whether in housing, financial capital, or digital infrastructure—demand governance models that promote inclusive resource distribution. The persistence of concentrated ownership in these domains mirrors past inequalities, reinforcing economic divides. Addressing these systemic issues requires equitable frameworks that prevent monopolization and foster widespread access to essential assets. As globalization intensifies land consolidation and the accumulation of wealth in smaller hands, history demonstrates that equitable resource distribution is a more effective driver of sustainable economic growth and resilience.

References

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. (2012). Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty. Crown Business.

Broadberry, S., & Gupta, B. (2006). The Early Modern Great Divergence: Wages, Prices and Economic Development in Europe and Asia, 1500–1800. Economic History Review, 59(1), 2-31.

European Commission. (2022). The Future of the Common Agricultural Policy: Rural Development and Land Use Policies in the EU. European Union Publications.

FAO. (2012). The State of Food and Agriculture: Investing in Agriculture for a Better Future.

GRAIN. (2018). L'accaparement des terres perpétrées par les fonds de pension dans le monde doit cesser.

Herlihy, D. (1997). The Black Death and the Transformation of the West. Harvard University Press.

IPBES. (2019). Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services. Bonn, Germany.

McBride, G. (1923). The Land Systems of Mexico. American Geographical Society.

Piketty, T. (2014). Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Harvard University Press.

Rothstein, R. (2017). The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. Liveright Publishing.

Saiz, A. (2010). The Geographic Determinants of Housing Supply. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 125(3), 1253–1296.

USDA. (2021). Farms and Land in Farms Report. United States Department of Agriculture.

World Bank. (2021). Land Governance Assessment Framework: Identifying and Monitoring Good Practices in the Land Sector.

Comments